When the Prime Minister Said, "They Really Love Interest", Everyone In Hungary Knew Who He Meant

- Stay updated on the latest news from Hungary by signing up for the free InsightHungary newsletter:

When Prime Minister Viktor Orbán said in a radio interview in late April that "they really love interest", he didn't specify who "they" were.

Orbán was speaking about a recommendation made by Hungarian-American financier and philanthropist George Soros on how the European Union might finance a €1 trillion coronavirus recovery fund. Soros proposed that the EU issue bonds for financing the recovery and pay interest in perpetuity, a recommendation Orbán called "the second Soros plan" as he lambasted the financier's plot to force European nations into "debt slavery".

"They really love interest," Orbán said. But who were they?

Orbán's comments, in the context of their reference to Soros, provides a clue. The billionaire has for years played a central role in the government's communication, representing a nationless "globalist agenda" which seeks to undermine the sovereignty of nation states, destroy Christian values and deliberately import millions of muslim migrants to Europe.

There has been a recent uptick in such sentiments by prominent Fidesz politicians and government-tied media figures. In recent weeks, a wave of references to a "network of globalist elites" spread across pro-government media. Government spokesman Zoltán Kovács twice referred to a "Soros cabal" in op-eds he sent to online newspaper EUobserver. The phrase was cut by the website’s editor-in-chief because, as he put it, “we don’t publish anti-Semitic conspiracy theories”.

As the Hungarian Forint weakened to historic levels this spring, conservative media and the public broadcaster speculated that Soros was “probably” betting against the currency. Orbán announced in early June that Soros will again appear in one of the government’s National Consultations, all signs that the billionaire is unlikely to drop from the headlines any time soon.

This portrayal of Soros and the shadowy cabal he purportedly represents have in recent years led to wave after wave of accusations that the Hungarian government was trafficking in veiled anti-Semitic messaging. But Soros’ demonization represents only the apotheosis of a complex history of overt and covert anti-Semitism within the Fidesz party that goes back years.

Trading Spaces

Fidesz’s association with anti-Semitism took on new dimensions after a fundamental change occurred in the Hungarian political landscape beginning in 2013.

Previously, the Jobbik party had provided Fidesz with a reliable buffer against charges of anti-Semitism. Open anti-Jewish statements and actions by Jobbik politicians meant Fidesz could credibly point to the party as embodying Hungary's genuine radical right.

The Euroskeptic, far-right nationalist party, which was aligned with the radical MIÉP in the early 2000s, has been described by the Anti-Defamation League as "openly anti-Semitic". In 2007, it formed a paramilitary wing called the Hungarian Guard, evoking Hungary's fascist WWII-era Arrow Cross party which killed and deported tens of thousands of Jews.

In 2012, a Jobbik MP urged the government to compile a list of Hungary's Jews, calling them "threats to national security", and in the same year, a Jobbik MEP was pressured by his party to resign his seat in the European Parliament after it was revealed he was of Jewish origin. One Jobbik MP was caught spitting on a Holocaust memorial in Budapest.

However, after taking power in 2010, Fidesz gradually adopted numerous key elements of Jobbik's platform: an adversarial approach to the European Union, praise for authoritarian systems like those in Russia and Turkey, and later, a hard nativist stance on immigration and refugees.

As the governing party took up ever more space on the nationalist right within Hungarian political life, Jobbik reacted to the encroachment by embarking on a campaign in 2013 to recast itself as a centrist people's party, a shift which continued throughout the rest of the decade. This attempt to rearticulate the party’s political identity, coupled with Fidesz’s steady march to to the far right, ultimately cemented Fidesz's control over right-wing populist issues and set the stage for the emergence of its own calculated anti-Semitic rhetoric.

Stop Soros

“We are fighting an enemy that is different from us," Orbán said during a speech weeks before national elections in 2018, and in the midst of a government campaign against the "Soros plan". "Not open, but hiding; not straightforward but crafty; not honest but base; not national but international; does not believe in working but speculates with money; does not have its own homeland but feels it owns the whole world.”

By 2018, campaigns against George Soros had become dominant central elements of the government’s platform. But the use of Soros as an evergreen national enemy began earlier, in 2013, and had origins in Orbán’s relationship with Israel’s Benjamin Netanyahu.

In the late 1990s, as Fidesz began its transition from a liberal youth party to the center-right, its attempts to consolidate Hungary’s right-wing vote led to the genesis of its association with anti-Semitism. According to a report by Direkt36, Fidesz kept its relationship with the openly anti-Semitic MIÉP party unclear ahead of elections in 2002 in an attempt to court its voters. No formal alliance was made, but the attempt to woo MIÉP voters led to damaging accusations by Hungarian liberals and some in the international press.

Orbán's failed re-election campaign that year later prompted him to seek a buffer between his party and charges of anti-Semitism, which he would find in an alliance with Benjamin Netanyahu, the leader of Israel's right-wing Likud party. In 2005, Orbán travelled to Israel to meet Netanyahu, then minister of finance, and began developing with him a political kinship which to this day has served to neutralize his party's reputation for anti-Semitism and bolster certain key parts of its political ambitions.

It was, ironically, this relationship with Israel and Netanyahu that laid the groundwork for Soros’ role at the center of the government's propaganda efforts. As Orbán prepared for a run for prime minister in 2010, Netanyahu introduced him to an American political consultant that had been instrumental in Netanyahu’s own successful run for prime minister in 1996.

The consultant, Arthur Finkelstein, was a well-known political operative who spent decades managing Republican campaigns in the United States. Known for developing a political method “that now reads like a how-to guide for modern right-wing populism", Finkelstein worked in secret to help Orbán win elections in 2010, giving Fidesz a two-thirds parliamentary majority which it has held nearly uninterrupted for the past decade.

Following the 2010 victory, Finkelstein continued consulting for the Hungarian government and, according to a sprawling article by Hannes Grassegger in Buzzfeed, helped devise a campaign in 2013 against Soros that would remain a central part of Hungarian political discourse for years to come.

Finkelstein reportedly saw Soros as a perfect enemy with which to mobilize voters to the Fidesz camp. According to Grassegger in Buzzfeed, Soros could be portrayed as "the puppet master. Someone who not only controlled the 'big capital' but embodied it. A real person. A Hungarian. Strange, yet familiar."

Since then, the government has spent tens of millions of euros of public funds on campaigns to portray Soros as the enemy of Hungarians, ascribing him nearly supernatural traits and alleging that he is the hidden hand of a shadowy network of "global elites" working to usher in a new world order.

The campaign began in 2013 with attacks in pro-government media on Hungarian NGOs allegedly funded by Soros, and a theory alleging that the billionaire was secretly directing the distribution of civil society grants provided by Norway. The accusations culminated in police raids on the offices of environmental organization Ökotárs, and while investigators found the NGO had committed no crime, the image of Soros as the head of an army of "Soros soldiers" had been successfully established, and the precedent for government targeting of NGOs would later lead to legal sanctions against them.

The Soros campaign was accelerated after the refugee crisis of 2015. The Hungarian government took the hardest stance in Europe against accepting refugees and asylum seekers, and soon, launched a campaign on the heels of the crisis which alleged that the billionaire was trafficking migrants into Europe and using his connections within the EU to force Hungary to accept refugees.

The crisis was also a turning point in the Hungarian-Israeli relationship: Hungary’s hard stance against African and muslim migrants, seen by many as xenophobic, was welcomed by the Israeli government. “Europeans are finally beginning to understand Israel, how it is for a Western country to live together with Muslims,” Likud’s Budapest-based international relations coordinator Tamir Wertzberger told Direkt36. The two countries’ conflicts with the EU made it “much easier for Hungary to support Israeli positions”, Wertzberger added.

The government's "Soros Plan" and "Stop Soros" campaigns in 2015-2018 were widely condemned as anti-Semitic by European officials, human rights NGOs and Soros himself, who said they were "reminiscent of Europe's darkest hours".

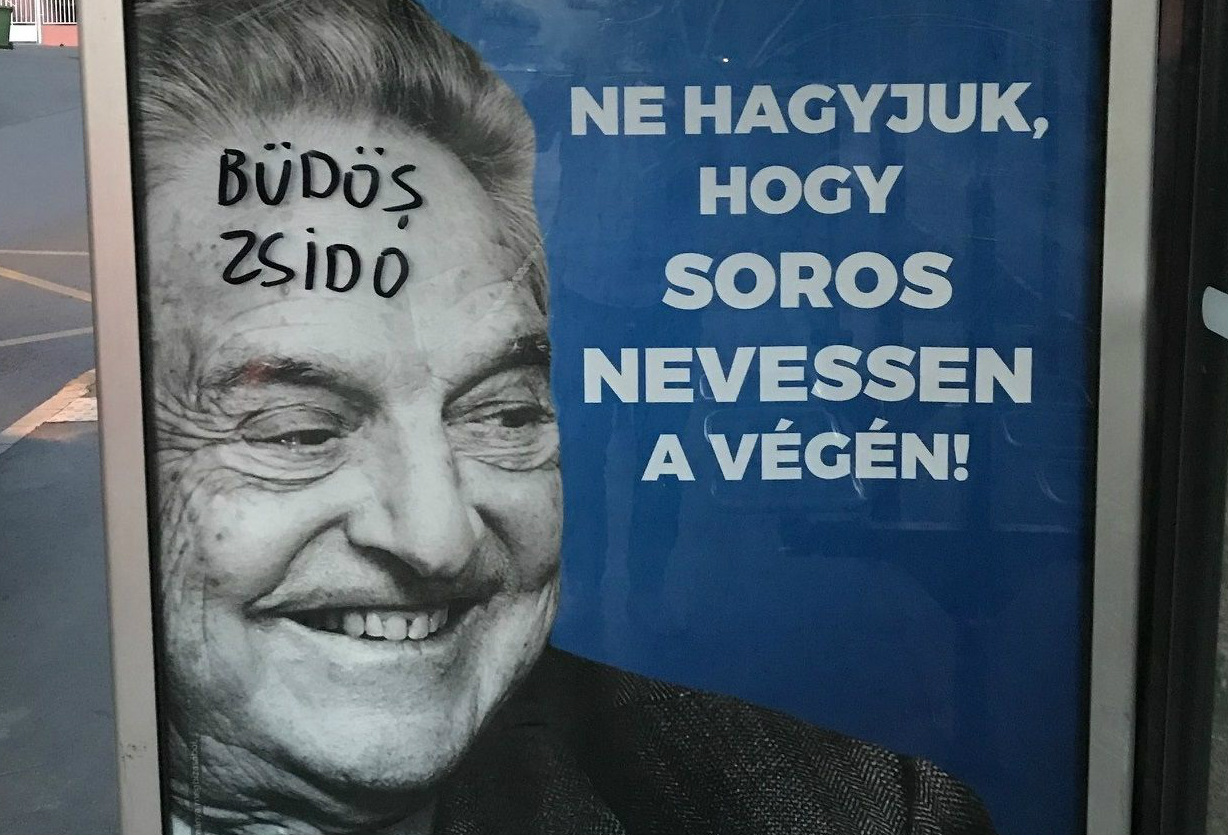

In 2017, the country was blanketed with posters and billboards depicting Soros' laughing face, many of which were defaced with anti-Semitic graffiti like "stinking Jew" and "vampire". Two such posters appeared on the floor of a Budapest tram where passengers could trample Soros' face. Hungary's largest Jewish organization said the campaigns "recalled Hungary's dark days", and that they fuelled anti-Semitic sentiment.

The Israeli ambassador called on Hungary's government to remove the posters and billboards, but one day later, Israel's foreign ministry retracted the criticism, reportedly on Netanyahu’s orders. An Israeli foreign ministry spokesman said the ambassador’s request was “in no way...meant to delegitimize criticism of George Soros, who continuously undermines Israel’s democratically elected governments”.

The Israeli prime minister intervening on Orbán's behalf, and the foreign ministry aligning with Hungary’s anti-Soros campaign, was a testament to their close ties. Haaretz has found that Hungary has the most pro-Israel voting record of any EU Member State, and in 2019, it became the first EU country to open a diplomatic trade office, an extension of its embassy, in Jerusalem.

This political kinship would be used to dismiss accusations of anti-Semitism against the Hungarian government. State Secretary and Orbán ally Vince Szalay-Bobrovniczky, in arguing against claims that the Soros campaigns were anti-Semitic, said at a conference in February that Soros is “persona non-grata in Israel… and nobody can call Israel anti-Semitic.”

Raining Cash

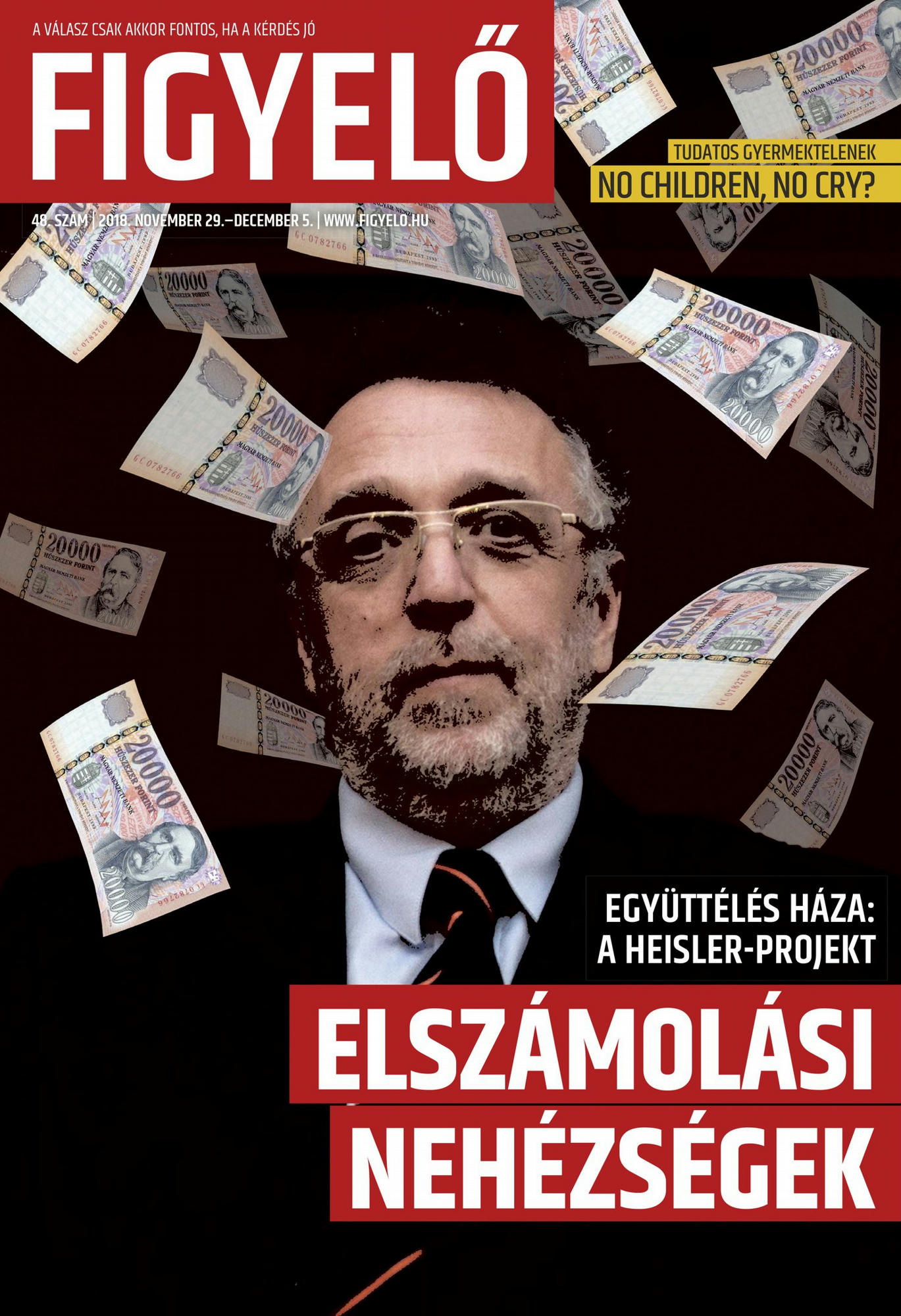

In November 2018, pro-government weekly magazine Figyelő published a cover featuring András Heisler, the head of Hungary’s largest Jewish organization, being showered with 20,000 forint banknotes.

The cover sparked outrage in Hungary and abroad, with Heisler’s organization, the Federation of Hungarian Jewish Communities (Mazsihisz), declaring it to be “anti-Semitic and frightening”, and “reviving centuries-old stereotypes against our community”. Ronald Lauder, president of the World Jewish Congress, urged Orbán to denounce the cover, and called it “the most disgusting hatred, worthy of the Nazi era”.

Orbán replied that he was surprised that Lauder would want him to limit freedom of expression and freedom of the press, and said Lauder had a “clear left-wing and liberal bias”.

The episode reflected a thorny political dynamic between Hungarian Jewish congregations and a government that often showed favor to Judaism’s more conservative manifestations.

Figyelő, the magazine which sparked the controversy, was then owned by the government’s prominent house historian Mária Schmidt, whose plans to open a new government-funded Holocaust museum in Budapest had been stymied in part by Mazsihisz’s refusal to participate. The group contested the proposed content of the exhibition, worried that Schmidt would seek to “whitewash” the Hungarian state’s role in the Holocaust and portray Hungary as a passive victim of Nazi occupation. The House of Terror, another state-funded museum where Schmidt is director, has long been accused of doing the same.

Construction on the House of Fates was completed in 2014, but it has yet to open due to the disagreements over its content. After András Heisler resigned from the museum’s advisory board and Schmidt was taken off the project, the government asked Rabbi Slomó Köves, leader of the Unified Hungarian Jewish Congregation (EMIH), to take control of the museum.

Köves’ placement at the head of the House of Fates is demonstrative of the government’s use of political alliances to negotiate delicate situations around Judaism. Much as Orbán’s political kinship with Netanyahu and Israel has provided him with credibility on questions of Jewish relations, the government’s mutually beneficial relationship with Köves’ conservative EMIH supplies an amenable alternative to the more liberal Mazsihisz.

The secular organization, representing the vast majority of Hungary’s liberal, Neolog urban Jews, has been outspoken in criticizing government policy toward Holocaust memory. Aside from its misgivings on the House of Fates, the organization has condemned Orbán’s praise as an “exceptional statesman” of Hungary’s wartime regent Miklós Horthy, a highly controversial, Nazi-allied figure who oversaw the passage of what are seen as the 20th century’s first anti-Jewish laws in Europe.

EMIH, which now represents the Jewish community in the House of Fates project, is affiliated with Chabad Lubavitch, an Orthodox Jewish Hasidic movement that has a few hundred observant followers in Hungary. Founded in 2004, the conservative group, which similarly cooperates with Netanyahu’s Likud in Israel, has developed a friendly relationship with the Orbán government since 2010.

EMIH’s head rabbi Slomó Köves campaigned for KDNP politician István Hollik in his 2018 parliamentary election bid. Köves also came to the defense of the government in 2017, declaring that the Soros campaigns were in fact not anti-Semitic.

Since 2010, the small congregation has received major financial support and free real estate from the government, including synagogues, schools, and a network of elderly care homes, among others. According to EMIH’s own financial declaration, between 2014 and 2018 it received €8.2 million in state support, not including the value of its free real estate and state-supplied loans.

In November 2019, the government granted EMIH special status, allowing it to receive additional special funding and grants for education from the government.

A Vanguard of Bigots

With well-established Jewish allies in Israel and at home, the appointment of controversial government allies to high-level positions seems to have accelerated in recent years. In the past 18 months, Hungary has bestowed state honors on a writer who claimed Hungary's WWII-era anti-Jewish laws were "in the Jews' interests", and to a literary historian who publicly questioned whether Imre Kertesz, the Nobel-prize winning Jewish writer and Holocaust survivor, could be considered a “Hungarian writer”.

Other virulently anti-Semitic figures have been elevated to prestigious government-financed posts. Sándor Szakály, a historian well-known for referring to the 1941 deportation and subsequent killing of Hungarian Jews as an “immigration procedure”, was appointed in 2014 to head Veritas, a historical research institute founded by the government.

The institute, tasked with “reevaluating the historical research of Hungary’s past 150 years”, has published papers seeking to resurrect the reputation of Regent Miklós Horthy. Szakály has recently argued that Hungary’s numerus clausus law, signed by Horthy in 1920 and which sought to reduce the number of Jews in Hungarian universities, could not be considered an anti-Jewish law.

In January of this year, Beatrix Siklósi, a Fidesz loyalist with a reputation for having extreme right-wing views and a tendency to post racist, anti-Semitic content and conspiracy theories on social media, was appointed to head public broadcaster Kossuth Rádió. Twenty-one Jewish organizations demanded her removal, but Siklósi remains in her post.

Previously, as editor-in-chief of Hungary’s public broadcaster, Siklósi was forced to relinquish control of the broadcaster’s religious content after the leaders of Hungary's historical churches wrote an open letter demanding her removal, citing her "overtly exclusionary and anti-Semitic remarks and statements".

Following surprise victories for opposition parties in the 2019 municipal elections, some Fidesz politicians were quick to blame the upset on the Jews. Fidesz vice-president Lajos Kósa declared that “the Jews were forced, or perhaps even enjoyed” electing a non-Fidesz candidate in his district - a comment for which he later apologized - , while house speaker László Kövér claimed the opposition had used “foreign-funded godlessness, treason, and denial of the nation” to win elections.

Fidesz co-founder and media personality Zsolt Bayer made a blog post in October with a photograph of a post box with numerous Jewish names written on it, suggesting that foreign Jews had registered in a single apartment in order to vote in municipal elections. Bayer has previously praised radical right-wing provocateur Zsolt Bede, whose website, Vadhajtások, routinely publishes openly racist and anti-Semitic articles. Several Fidesz politicians have in recent months posted articles from the fringe website to their social media pages.

. . . . .

These years of playing off of existing social prejudice have been accompanied by a shift in voter attitudes toward Jews. According to a report on anti-Semitic sentiment by the Action and Protection Foundation (Tett és Védelem Alapitvány) and pollster Medián, the proportion of Hungarians that demonstrated strong cognitive anti-Semitic prejudice increased from 11 percent to 21 percent between 2013 and 2018, while the number of Hungarians saying they believe in a “Jewish world conspiracy” doubled between 2006 and 2018.

The Anti-Defamation League found that the number of Hungarians harboring anti-Semitic attitudes went up by nearly 100,000 between 2015 and 2019, and a 2018 poll by CNN found that one in five Hungarians have an unfavorable attitude toward Jews.

While many of Orbán’s critics agree that the prime minister does not personally harbor anti-Jewish animus, a combination of political calculation and strands of genuine anti-Semitism within his party have stamped it with a reputation that no alliance with Israel is likely to soon erase.