Index and Independence: How Hungary's Leading Outlet Became the Target of Political Control

- Stay updated on the latest news from Hungary by signing up for the free InsightHungary newsletter:

Vice President of the European Commission for Values and Transparency Věra Jourová sent a letter on July 7 to Index.hu, Hungary’s largest online news portal, expressing her solidarity with its staff which she said “has been working under very difficult conditions”.

Jourová wrote that while media revenues have been heavily hit by the coronavirus pandemic, “economic pressure should not turn into political pressure...I have been following the situation of Index with concern. What you are doing, the values you are fighting for, media freedom and pluralism, are essential for democracy.”

The letter came amid what Index considered a fight for its existence. In late June, an urgent public statement signed by around 100 editors and journalists raised the alarm that the site's independence had come under attack, and that the outlet was in "grave danger".

To many observers of Hungary's media environment, the news came as little surprise. It was widely considered only a matter of time before the outlet faced attacks on its editorial independence, an expectation engendered by years of other Hungarian websites, newspapers, television networks and radio stations being shuttered or suddenly transformed under political and financial pressure.

This year, media watchdog Reporters Without Borders, which has described the level of media control in Hungary as "unprecedented" in the European Union, ranked the country 89th in the world for media freedom, down 33 places from when the organization began its rankings in 2013. Additionally, the U.S.-based non governmental organization Freedom House gave Hungary a score of two out of four for media freedom and plurality this year.

Despite this media environment and a perpetual struggle to preserve its independence, Index has, somewhat paradoxically, managed to remain the most-read and one of the most trusted news sources in Hungary for the past 20 years. It has maintained its critical reporting even as government-tied businesspeople were embedded in its ownership structure, and has walked a tightrope between its journalistic principles and a deep uncertainty over when, and how, they might be curtailed.

This constant vulnerability, and the ways Index’s newsroom has successfully struggled to retain its independence while so many other Hungarian outlets could not, are illustrative of the broader mechanisms that have undermined media plurality and freedom in Hungary for the past decade.

“Index Is In Danger”

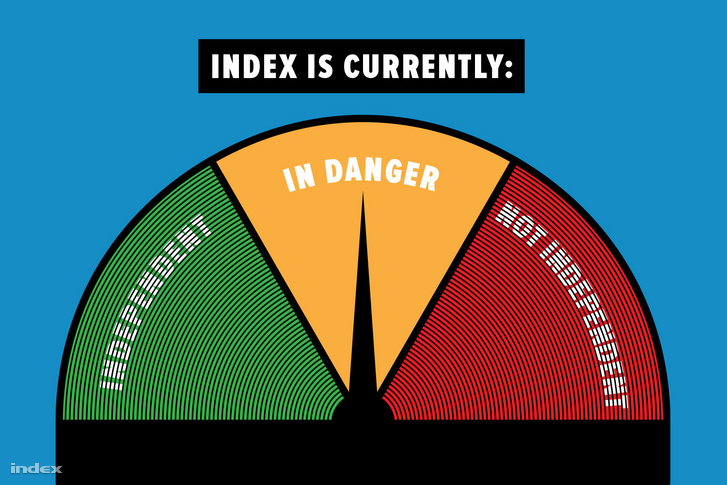

Two years ago, staff at the outlet established an online independence barometer, a means of directly addressing readers on the status of Index's editorial independence. The barometer was set up after a government-tied figure purchased a stake in the company that controls Index’s revenue stream, and was emblematic of the perceived inevitability of an attack on the site. At the time, a letter to readers said that staff felt they were “stuck on the frontline of a world war. Sometimes it’s the Red Army, sometimes it’s the Wehrmacht that marches over us.”

For the two years since its inception, the barometer read “Independent”. But on June 21, for the first time, staff moved the dial to "In Danger".

The change came after a series of board meetings of Index’s parent foundation, where a recommendation was made by an outside advisor to break up the site and outsource its content creation to external, newly-formed companies.

The proposal, ostensibly a response to economic pressure caused by the coronavirus pandemic, alarmed several members of the board of directors, including editor-in-chief Szabolcs Dull and CEO András Pusztay. In a statement, Dull wrote that Index was “under such external pressure that could spell out the end of our editorial staff as we know it. We are concerned that with the proposed organisational overhaul, we will lose those values that made Index.hu the biggest and most-read news site in Hungary.”

When news of the proposal leaked in the media, Dull was suspended from the board of directors. A few days later, Pusztay resigned as CEO, saying he could not in good conscience carry out the orders which had been placed on him. Since then, the newly-appointed CEO resigned after less than a week on the job, and another external advisor has recommended Dull’s removal as editor-in-chief.

These disruptive events and proposals by government-tied advisors alarmed Dull, Pusztay and many staff members on their own merits, but the circumstances’ similarities to earlier takeovers of critical media outlets likely added fuel to their suspicions. The events at Index, and some of the actors involved, fit a pattern going back years that illustrates a cohesive strategy for building a media environment that can be managed from the highest levels of political power.

The Usual Suspects

In March, an influential figure in pro-government media enterprises purchased a 50 percent stake in Indamedia, the company which controls all of Index's revenue streams and has exclusive rights to manage its advertising. The arrival of Miklós Vaszily in Index’s innermost circumference caused new concerns that government-tied figures were closing in on the outlet, evoking alarming memories of an earlier event involving Vaszily that sent shockwaves through the Hungarian media market.

In 2014, Vaszily oversaw the dramatic takeover of Hungary’s then-largest online news outlet Origo, where he served as CEO. Origo’s reporting on cases of corruption within the government, especially concerning two high-level ministers from the governing Fidesz party, reportedly angered party officials and led to political pressure being placed on the outlet’s parent company.

Vaszily is widely thought to have acted on the government’s behalf to facilitate changes at Origo that resulted in the dismissal of the site’s editor-in-chief and the resignation of more than 30 journalists over what they considered a pro-government shift in editorial direction. Once a producer of quality investigative journalism and reportage, Origo is now considered by many to be a government mouthpiece.

Following the takeover of Origo, Vaszily quickly rose through the ranks of government-tied media. He was appointed CEO of Hungary's public broadcasting organization MTVA (itself deeply loyal to the Fidesz-led government), and later became the CEO of Echo TV and the chairman of TV2, both owned by Lőrinc Mészáros, an oligarch and personal childhood friend of Prime Minister Viktor Orbán. According to reporting by 444’s Pál Dániel Rényi, Vaszily is known to have connections with the highest levels of government, and meets personally with Mr. Orbán to discuss important issues.

His important role in the government-tied media landscape and involvement in the Origo affair made Vaszily’s entrance in the ownership structure of Index seem to portend a future for the outlet which could echo Origo’s fate.

Origo’s 180-degree turn serves as a template for how government loyalists have repurposed critical media in the service of political interests. Often, rather than hostile legislation or direct intervention being used to transform an outlet, changes in ownership and financial pressure have been applied to indirectly shift outlets’ editorial direction, insulating the government from direct involvement. Financial "reforms" are thus used to justify takeovers under the banner of simple commercial efficiency.

These same arguments are now being used to account for changes at Index: Vaszily has denied he intends to muzzle the outlet, but insists economic problems must be addressed – despite the site’s position as the leader on the Hungarian media market.

Undermining media independence using financial “reforms” is a model that has been frequently used since 2010, although more aggressive methods including outright closure have also been employed. In 2016, Hungary's most-read daily newspaper Népszabadság was suddenly shut down following the acquisition of the paper’s publisher by an Austrian businessman with ties to Fidesz. Staff arrived one morning to find they had been locked out of the building, and could access neither their company email accounts nor the paper’s website. The closure, which staff described as a “coup”, made international headlines and resulted in a wave of street protests for media freedom, but the paper’s publisher insisted the decision was purely economic, and that the paper had been struggling financially.

Another means for seizing control of the media has been the generous use of government advertising in friendly publications and the withholding of ads in critical ones, heavily distorting the media market and putting financial pressure on independent outlets. Nearly 90 percent of ad revenues in the Fidesz-tied newspaper Magyar Idők came from ads paid for by the government in 2017, compared with 3 percent in the conservative Magyar Nemzet (which was government-critical at the time but has since been recaptured). According to editor-in-chief Dull, Index receives practically none of its ad revenue from the government.

Such methods for media control, which have now become commonplace, first began with Fidesz’s entrance to power in 2010, and represented a dramatic interruption of some 20 years of relative balance and development in Hungary’s media market following the collapse of socialism in 1990.

Paradise Lost

At the time of Index’s founding in the late 1990s, Hungary was entering a period of hopeful optimism following a decade of uncertainty and economic decay that came after what Hungarians call “the system change”, the country’s democratic transition after 1989. The internet was just taking off in the country, and for many, Index was symbolic of the highest hopes for what this new technology, new political freedoms and market capitalism would mean in this burgeoning era.

As the site grew throughout the early 2000s and Hungary joined the European Union in 2004, a new generation of Hungarians believed that the country was on an inexorable trajectory toward the West’s economic prosperity and democratic rule of law. Index, therefore, was associated not only with a new age of a free Hungarian press, but as a harbinger of the stable, pluralistic political system and democratic institutions sure to come.

Then, in 2010, Fidesz and Viktor Orbán won a two-thirds majority in parliament which they have held practically uninterrupted ever since. Determined to hold its newly-won power indefinitely (Orbán famously said before the elections, “We only have to win once, but then properly”), the party set about reshaping Hungary, and the media, in its favor.

At the center of this post-2010 transformation was businessman and media tycoon Lajos Simicska, an important ally and advisor to Viktor Orbán and the one-time architect of Fidesz's vast financial hinterland. Simicska's media holdings, which included the popular daily newspaper Magyar Nemzet, television network HirTV and radio station Lánchíd Rádió, provided a reliable and integrated network of outlets that portrayed the new Fidesz government in a positive light and controlled access to damaging information, reportedly under direct government supervision.

But in 2015, a very bitter and public falling out occurred between Simicska and Orbán, reflected by a sudden change to the editorial stance of Simicska’s media holdings. In a powerful display of the political flexibility of the Hungarian media, both Magyar Nemzet and HirTV became distinctly government-critical as Simicska, who began espousing the radical right-wing Jobbik party, carried out a personal campaign against his former ally Orbán. Soon, the entire leadership of his media outlets resigned “for reasons of conscience”, and Simicska carried out a purge where he vowed to fire every “Orbánist” in his employ.

The outlets functioned for another three years, and due to their newly-adopted government critical tone, were considered to have become part of the “opposition media”. But two days after Fidesz won another two-thirds majority in 2018 parliamentary elections, Simicska dissolved Lánchíd Rádió, and shuttered Magyar Nemzet after 80 years in print.

The major transformations at these and other outlets at this time demonstrated some newsrooms' lack of resilience to the political will of their owners. Just as Origo became a government mouthpiece and Népszabadság was simply shut down (despite major protests and remarkable efforts to save the outlets by editors and journalists), so did Simicska's publications undergo sudden and radical shifts in a government-critical direction after he fell out of favor with the prime minister.

When the tycoon no longer considered it possible to settle his political scores using his media organizations, many were liquidated. In an apparent act of capitulation to Orbán, Simicska ceded the remainder of his media holdings to Fidesz loyalists. The ninth richest Hungarian in 2016, Simicska now lives quietly as the country’s 49th richest man.

Another Bargaining Chip

Index has not been exempt from these turbulent power dynamics, but it’s status as an element of key importance in the Hungarian media landscape is partly due to its ability to weather such political tempests and maintain its editorial independence, even as political actors have eyed it as a potentially powerful acquisition.

Politically connected figures have lurked in the outlet’s ownership structure since 2006, when it was purchased by Zoltán Spéder, a banker and businessman with close ties to Fidesz which was then in opposition. After Fidesz won a two-thirds parliamentary majority in 2010, Index staff worried that Spéder had begun exerting political influence on the site, prompting editor-in-chief Péter Uj and many other Index journalists to leave the organization in 2011 and go on to found 444.hu in 2013. (The author of this article also works in association with 444.hu)

It was at this time that Fidesz launched a coordinated effort to broaden its influence in the media ahead of national elections in 2014. To that end, Simicska, who already had control of numerous media assets, secretly signed an option to purchase Index from Spéder in 2014. Additionally, Simicska signed another purchase option for TV2, and Népszabadság, as well as nearly two dozen regional daily newspapers, were transferred to the Fidesz-connected Austrian businessman Heinrich Pecina, who would later be implicated in Népszabadság’s demise.

Index thus found itself in the hands of one Fidesz ally while the party’s own in-house media tycoon held an option for its purchase. Spéder, who had grandiose business ambitions, depended on his good relationship with Fidesz for his success, and was said to occasionally exert pressure on the newsroom concerning stories of particular political importance. Still, Index staff fought to maintain their autonomy, and the site was considered critical and independent.

Similarly to Simicska, Spéder’s overzealous ambitions led to his own falling-out with the prime minister in 2016 when he became the subject of a relentless media smear campaign. His home was searched by police, the offices of his bank FHB were raided, and his businesses were investigated and audited by authorities. As 444's Pál Dániel Rényi reports, Spéder had only two choices in 2017 as it became clear his banking and media empire were falling: to hand Index over to Orbán allies, or allow Simicska to exercise his purchase option. Spéder chose the latter.

Simicska's purchase of Index caused shockwaves within the organization, and many feared the outlet would become another casualty of Fidesz’s internal political battles. But Index was a market-leading media product, and if Simicska were to weaponize it as he had done to Magyar Nemzet and HírTV, readers and journalists would have lost confidence in its value. To avoid such a scandal and potential financial catastrophe, Simicska immediately placed ownership of the outlet into a foundation – where it remains to this day – which would ostensibly insulate it from political control.

While the foundation and its board of directors were able to protect Index’s editorial independence, the site’s financial reliance on its ad manager Indamedia presented a lasting vulnerability. In late 2018, a 50 percent stake in Indamedia was sold to businessman Zsolt Oltyán, a politician with Fidesz's minority partner KDNP.

According to Rényi, it was inconceivable at the time that Oltyán and his purchasing partner could have bought one of Hungary's leading media companies, worth some €8.5 million, on their own volition and with their own money. The purchase led Index staff to launch the site’s independence barometer as a means of directly informing readers whether a genuine political takeover had occurred in its newsroom.

In March of this year, the day after the Hungarian government announced a state of emergency and granted itself extraordinary powers to rule by decree, Oltyán sold his 50 percent share in Indamedia to Miklós Vaszily. Soon after Vaszily’s acquisition, external advisors were hired at Indamedia who proposed Index’s breakup, leading to the current crisis.

…..

As of this writing, it remains unclear what will become of Hungary’s largest online news outlet. Index is currently operating without a CEO, and although the advisor that originally proposed the site’s breakup was dismissed amid the controversy, many critics maintain that the site remains under threat and that the ultimate goal is to throttle its critical voice.

Meanwhile, no one seems to know who is ultimately responsible for the disturbances: all relevant parties have sought to demonstrate that their hands are clean. Miklós Vaszily told 444’s Pál Dániel Rényi that he has “no intention of making a second Origo” out of Index, and in an email to InsightHungary, Vaszily wrote that he has no operational role in Indamedia and is “not involved in the life of Index.hu. [I am] practically...watching it totally from the outside.”

The Hungarian government did not respond to a request for comment, but Hungary’s media authority NMHH told InsightHungary that a report can be filed on any suspicion of media rule violations but that no report has been filed in the case of Index. There is, after all, no law prohibiting the purchase of stakes in a media company.

This article is published as part of a project to promote independent digital media in Central and Eastern Europe funded by the National Endowment for Democracy and coordinated by Notes from Poland.