Conservative backlash against women’s rights in Hungary

- By Kinga Rajzak

Over the past decade a growing narrative has gained traction in Hungary, calling on women to embrace their fate as homemakers and caretakers as Prime Minister Viktor Orban, the self-appointed defender of Europe’s Christian values has steered the country towards a conservative, in his words “illiberal democracy.”

“It is an undisputed truth that the world belongs to those who populate it,” said Laszlo Kover, speaker of the National Assembly in October, as he pleaded with women to follow their calling as mothers for the nation’s survival. “Those who don’t want children choose a path of self-annihilation.”

Kover’s remarks came on the heels of Hungary’s co-sponsorship of the Geneva Consensus, an informal declaration that has pledged to protect life from its conception, thereby condemning abortion. Other notable proponents of the symbolic manifesto included the United States as a fellow co-sponsor and Poland, the latter being the only other European signatory.

Critics say that backing the treaty is a bold political move that contradicts public sentiment, and points to a larger problem at the heart of Hungarian politics.

“Research shows that anti-abortion measures have no public support,” said Rita Antoni, chair of Nokert Egyesult (For Women Organization), a women’s rights lobby group. “Orban knows that limiting access would deal a blow to his rule, yet here we are.”

According to a 2013 poll, 53 percent of those surveyed were content with Hungary’s abortion law, while additional 18 percent said that they would even ease restrictions around it. Only 13 percent wanted to see abortion overturned.

“It is just another move to chip away at women’s rights,” said Gyorgyi Toth who is a life-long activist and volunteer trainer at NANE, Nok a Nokert (Women for Women) organization that offers support to victims of domestic violence. “Not that it was ever great to be a woman in this country.”

Toth says that the number of women in leadership positions, particularly in politics is a good indicator of a nation’s health in terms of gender equality.

“You would have thought that after the Soviet regime fell, we were going to see more liberal women’s rights initiatives, and altogether more women across the social and political spectrum, but clearly that was a pipe dream.”

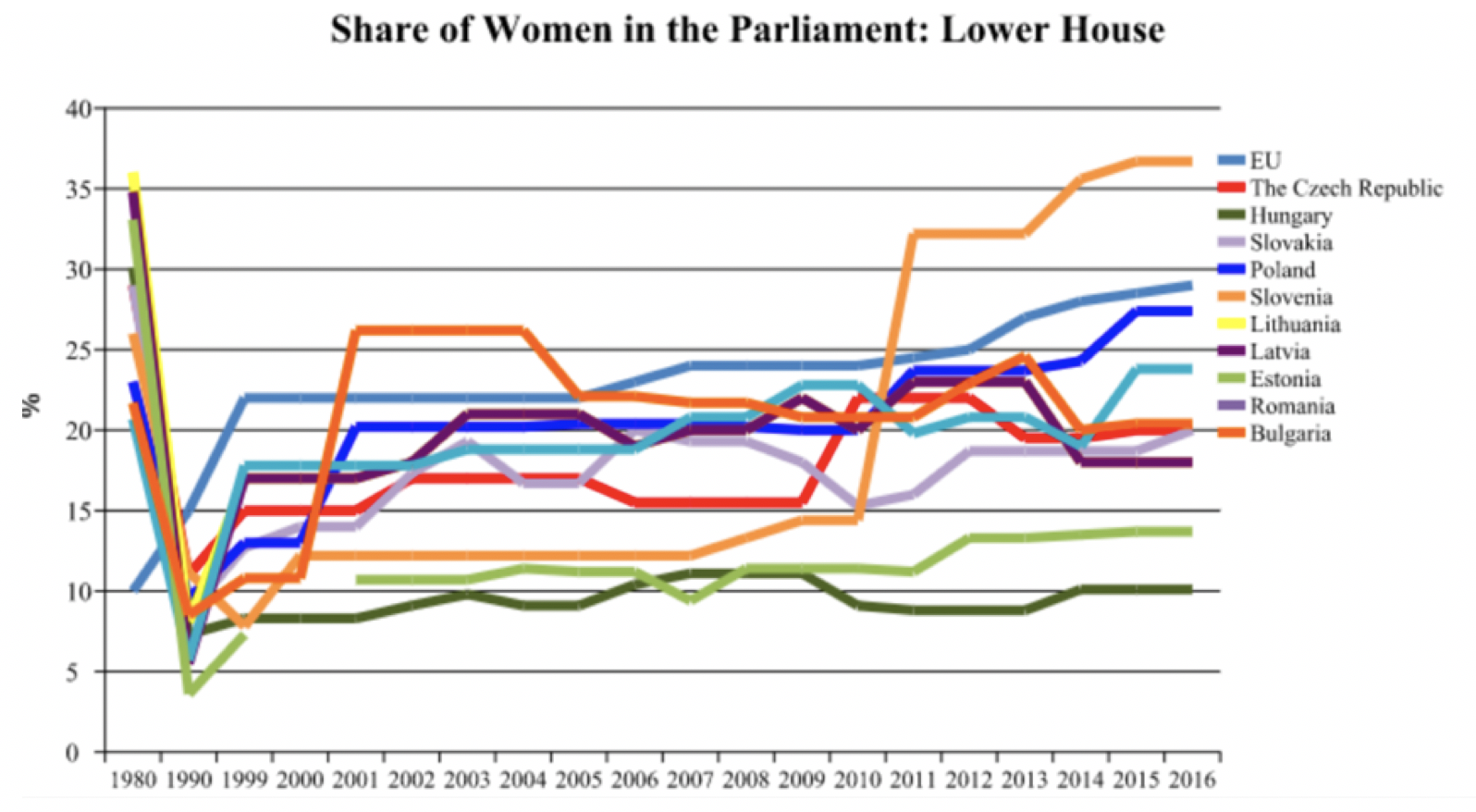

Leading up to the fall of Communism, Hungary, like the rest of the Eastern Bloc seemed progressive from a feminist standpoint with female representation in the parliament at 30 percent, projecting a growing gender equality only to be exposed in the ‘90s as a mere masquerade.

Once the Iron Curtain crumbled in 1989, and deceptive quotas vanished, women disappeared from politics almost overnight.

Like Hungary, neighboring post-Communist countries saw a sharp decline in the number of women in office but have worked on getting more women into public life ever since. While others progressed, Hungary has fallen behind, and to date has the lowest number of female MPs compared to its post-Soviet peers.

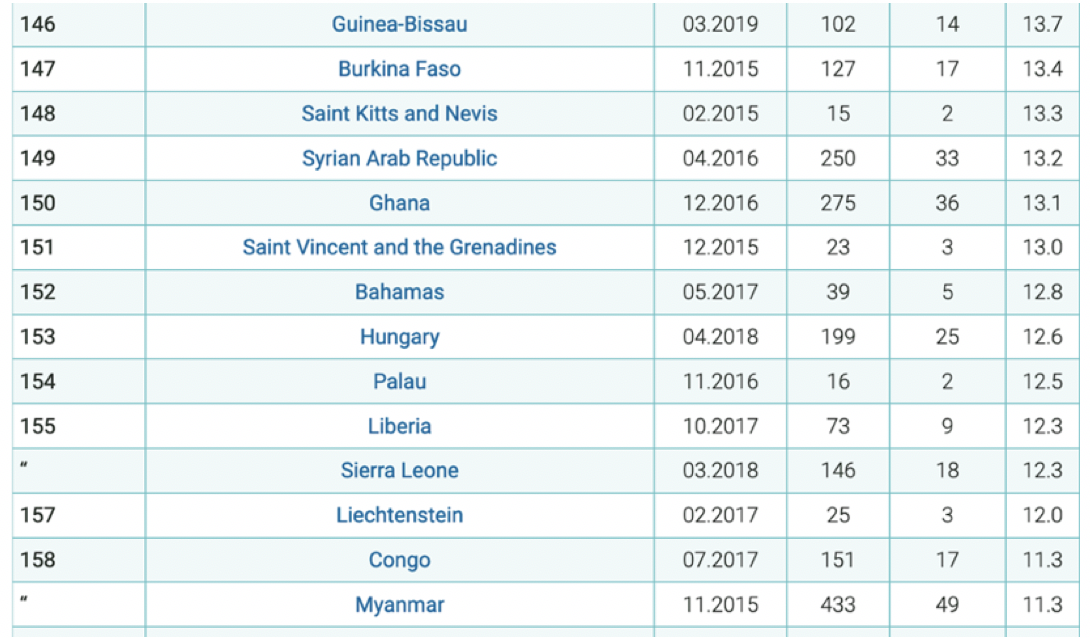

In an international survey Hungary was at the bottom of the list as well.

The 2019 global data for national parliaments ranked Hungary at 153 for having only a handful of women – 12.6 percent – in public office.

“You need to look at the context to understand how we got here,” said Toth. “After the Iron Curtain fell, everyone wanted something new, but they didn’t know exactly what.”

It was at this time that Fidesz (Alliance of Young Democrats), founded by Orban and a group of progressive hopefuls appeared on the political stage. They promised to do away with post-Communist demons and make Hungary more liberal, following pro-Western values.

In 1990, Orban said, those who interfered with women’s reproductive rights “were not human beings but monsters,” echoing his ally, Laszlo Kover who said, suspending abortion access would be equal to enforcing religious observance onto citizens.

“Soon after the Communist regime crumbled, it became obvious that there wasn’t going to be a sweeping political change that would benefit women,” said Toth who joined NANE in 1998, at the time when Orban won his first mandate. “Those politicians who sympathized with women’s rights didn’t offer feasible programs that would have led to gender equality.”

She says, the biggest most obvious rhetorical shift came with Orban’s second mandate in 2010, when he won parliamentary majority with the Fidesz- KDNP (Christian Democratic People's Party) ticket.

Orban’s alliance with the Christian democrats foreshadowed an ideological about-face and the emergence of a more conservative mindset.

“Orban sniffed out that Hungarians wouldn’t vote for progressive measures, as it was incongruous with our past,” said Antoni. “He might have changed ideologically, but it is more likely that he wanted to secure a political power grab.”

Antoni says that Orban’s use of sexist, homophobe, transphobe rhetoric can be attributed to his desire to shore up support among those who feel threatened by minorities, yet the PM’s offhand chauvinism targeting women is harder to understand.

“It makes no sense to suppress women when half of your population is made up by them,” said Antoni. “But in his world, women have no say or place in public life, since they belong in the kitchen.”

In 2020, Hungary ranked 27 for gender equality in the EU, four places down from 2013.

The pro-Western liberal ideals once embraced by Orban have morphed into adverse abstractions; ‘gender,’ as a word itself becoming the focus of much dispute some twenty years later.

In 2018, the government suspended gender studies at colleges, and this spring, banned changes to a person’s sex recorded at birth, thus boycotting transgender rights. In November, the legislature also proposed a constitutional amendment that stipulates that children must be raised with the “Christian interpretation of gender roles” and their “gender identity at birth must be protected.” The bill also states that family means that “mother is a woman and father is a man.”

“We don’t use the word gender in Hungary,” said Orban in Brussels this fall, as he buckled down to explain his gripe with the term, subsequently starting a lengthy debate with EU lawmakers. “People are born either female or male.”

The PM noted that ‘gender’ was an ideologically overloaded word, something of “western export” that had an underlying agenda to destabilize decency and lead to queer identity categories.

Toth says that the government’s latest measures undermine the rights of women and minorities and make it harder to challenge gender stereotypes and patriarchy.

“I don’t deal with women’s issues,” quipped Orban when journalists demanded answers for Reka Szemerkenyi, former US ambassador’s demotion who was replaced by Orban’s ally, Laszlo Szabo.

Critics were quick to point out that Orban had directed multiple jabs at women over the years, calling into question their acuity to serve in office, and saying that women were too sensitive to cope with the cut-throat atmosphere in politics.

“Women don’t have the posture to withstand the character assassination that goes on here,” said Orban in 2015.

The Chair of the Hungarian Women’s Lobby, Reka Safrany disagrees.

“Politics is artificial, not a dog-eat-dog realm by nature, so it is only hostile if we make it so.”

Safrany spearheads an umbrella organization that is inclusive of women’s rights non-profits. She says, they get a lot of messages from women from around the country about all sorts of issues, which they pass on to NGOs that start a public conversation and push for new laws. Over the past decade, however, women’s rights initiatives are coming up short, if not ignored by the government.

“Orban has consciously moved towards creating a macho country that permeates every tenet of life from the social to the political,” said Safrany.

The obvious problem, according to her, is with the government’s masculine swagger from glorifying and pouring orbital sums into soccer, to always looking for enemies let it be migrants, Soros or Brussels; simultaneously in this system women are passive actors, having no say, after all they are seen as second-class citizens with one type of calling, giving birth.

“I’d like to have an agreement with the Hungarian ladies, and their role in the nation’s future,” said Orban in 2018, as he ruminated on Hungary’s fate. “Child-bearing is a private matter, but also a very public one.”

As Hungary’s neonatal numbers have dropped and demography has plummeted, the government has called on women to do their job for clan and country. But Safrany says, this shouldn’t be the reason to view women as “machines,” destined to bear children.

“The fact is, it takes two to tango, and nobody talks about the men as fathers and their role in raising kids.”

A 2018 EU study revealed that in Hungary, 41 percent of men interviewed thought that work-life balance was hard to reconcile with child-raising, and only a third of them said that they would opt for a paternity leave if given the choice. Meanwhile, the very same percentage of people also thought that any hiatus from work would negatively impact their careers. However, 49 percent said it was easier for women to give up their professional pursuits and stay home.

Over the past years, the government has introduced a slew of tax incentives and beneficial, competitive mortgage rates that are available to married couples who decide to have multiple children.

Those families who have one child can apply for an interest-free 10 million Ft (30,000 EUR) government subsidized loan which doesn’t have to be paid back if the couple goes on to have three kids. Married women can altogether give up paying personal income tax if they have more than four children. Then there is a mortgage for expecting families called ‘Babavaro hitel,’ and an array of other offerings, including a non-reimbursable 2.5 million Ft minivan aid for large families.

But there is a catch, says Safrany.

While these various benefits sound attractive, only those families who earn enough will make the cut and qualify for the loans, so by proxy these measures benefit the middle-class, not poor people or minorities.

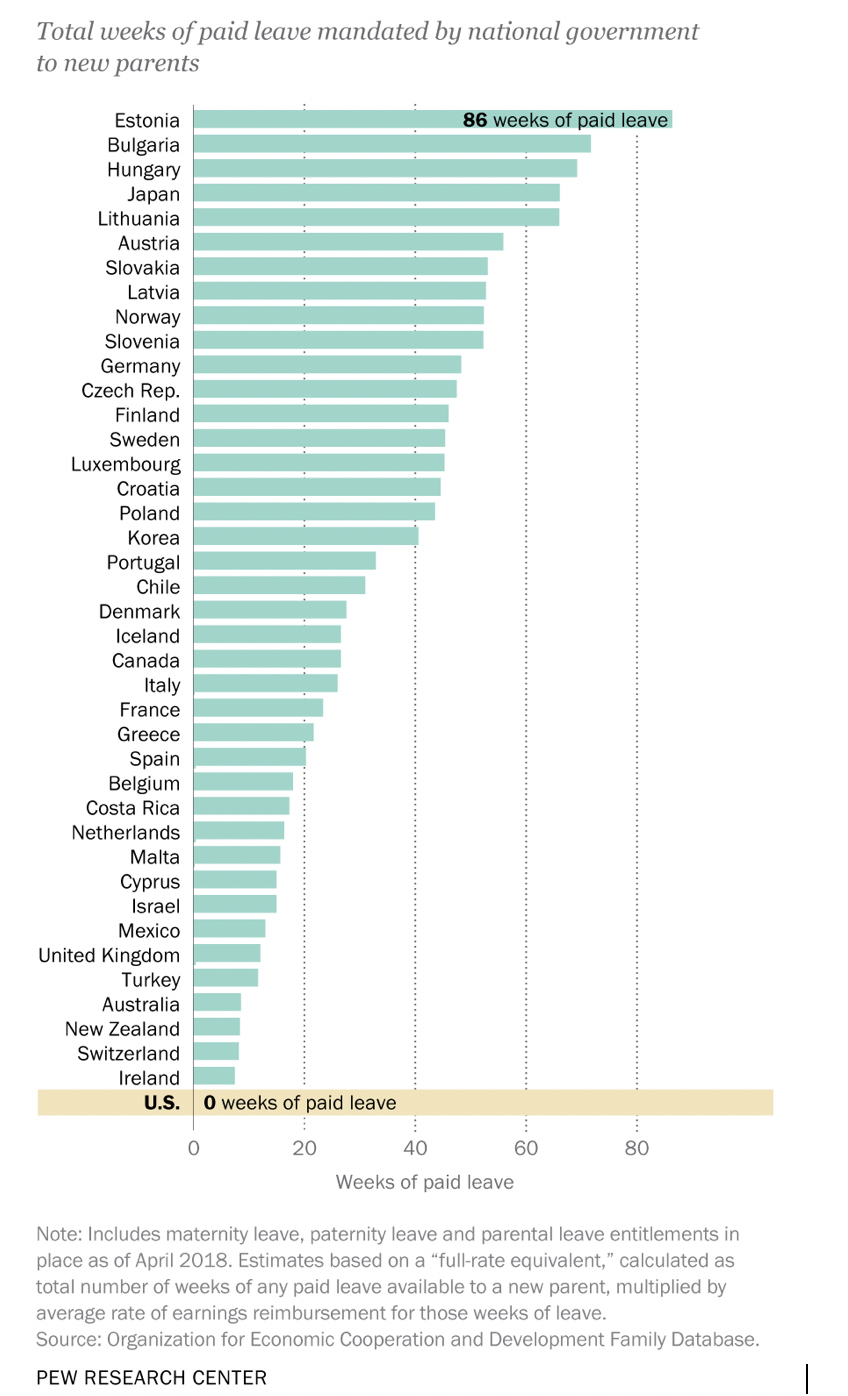

A 2018 Pew Research put Hungary at the third place in the world for guaranteeing the longest paid parental leave – 70 weeks – which Safrany says is great for cementing the mother-child relationship, but a real hindrance if women want to return to the job market.

Then there are other problems.

Domestic violence is rampant in Hungary, yet authorities are not doing enough to protect women.

The reason is self-evident, said Safrany. “In a Christian conservative patriarchal society, it is undecipherable to come to terms with the father, the breadwinner being the abuser.”

Antoni said that one would assume that the government’s plea to women to have more kids meant that the country “rolled out the red carpet” for them, providing protection, respect and institutional support, but this was not the case.

In May 2020, at the height of the Coronavirus pandemic, Hungary announced it would not follow the EU and 35 other countries in ratifying the Istanbul Consensus, a de facto gold standard providing a plan and legislative guidance to protect women against domestic abuse.

“It was one thing that we signed it previously,” said Toth. “We would have had to ratify it, and keep ourselves to it as well, which in this toxic climate would have been difficult.”

Toth says, a record number of women call NANE’s hotline at any time seeking help, and the coronavirus pandemic has made things worse as victims find themselves wedged between four walls with their abusers.

Judit Varga, Minister of Justice and a faithful Orban ally said that the Istanbul treaty reeked of murky liberal language that offered protection to migrants – personae non gratae in Hungary – and drew on the word ‘gender,’ a dubious term that potentially promotes homosexuality.

She said that the country had enough safety nets for women and didn’t need another one just to be policed by Western powers.

“You shouldn’t fear being killed by your partner,” said Toth, and pointed to the government's lax attitude to deliver comprehensive laws to fix the problem.

“Victim blaming is the most obvious response, that’s why most women don’t report the abuser or simply bleed out trying to seek justice.”

But there are exceptions, and Erika Renner’s story is a good example.

“I had to go through the legal ordeal, not only for myself, but for other victims.”

- The story of Erika Renner

On a Tuesday morning in March 2013, Erika Renner was getting ready to take her dog for a walk. Her teenage children just left for school. It was 7:30 am.

She opened the door and was about to step out when a figure, clad in black wearing a bicycle helmet leaped forward and pushed her back into the apartment.

Before she knew it, she was tied up on the bed and intravenously sedated. The perpetrator then removed her clothes, put her in the bathtub and poured acid over her genitalia. He then carried her back to the bed, untied the unconscious Renner and took the batteries from her phones, scooped up her laptop and made for the door. As he left the apartment and hurried down the stairs, he bumped into a neighbor just as he unbuckled his helmet gasping for air.

It was Renner’s ex-boyfriend, Krisztian B., pediatric burn specialist and director at Irgalmasrendi Hospital.

Shortly after the crime, Renner was found by her ex-husband who took her to the hospital with permanent genital tissue damage caused by three-degree burns. The very same day police arrested the perpetrator and found a syringe in his car laced with the sedative used on Renner. Evidence was brought forward, and prosecution began by the authorities.

Then a strange thing happened.

Given the identity of the perpetrator whose brother was a high-level official in the Fidesz government, the chief prosecutor wanted to stop the case. He cited lack of proof as hard evidence was left out from the deposition. Renner then had to hire a private lawyer and appeal. It took her over seven years to see justice. The discovery was delayed as investigators tried to discredit her words and downplay her injuries.

“The genital burns were categorized as minor and machine-related, as if I got them in a factory,” said Renner. “Despite the expert medical opinion and hard evidence, the truth was inconvenient for the prosecutors, because to them, a well-connected man in a suit with an IQ over 150 had to be innocent.”

During the litigation the defendant was free and allowed to practice medicine. He had been released just after three months following his arrest.

“He destroyed my life,” said Renner. “For months, I had to wear a diaper. I knew, I would not have a healthy, normal sexual life anymore, and there he was, walking around as if he had done nothing.”

As the court case dragged on, the defendant started to stalk Renner again, so authorities assigned a 24-hour security detail, still she didn’t feel safe.

In 2019, after years of endless litigation and multiple guilty verdicts, Hungary’s supreme court, the Curia affirmed and amended the ruling by the lower chamber and sentenced the defendant to 11 years without the possibility of appeal.

Parallel to the criminal investigation, Renner also filed a civil lawsuit demanding that the defendant pay 25 million Fts for her surgeries, psychological counselling and legal defense that had set her back 17 million Fts. The defendant, however, has signed over his wealth to friends and family, so Renner needs to start litigating again if she wants to see the money.

“The whole ordeal cost me a lot, ironically I had to pay up to see justice,” said Renner. “But throughout the whole case, I kept thinking that I’m also doing everything for the nation, for other victims. That my case will set a precedent.”

According to the latest EU survey, about 75 percent of the population in Hungary thinks that domestic violence is a widespread issue, but over 60 percent believes that the country has adequate laws to protect women against abuse.

“The legal system is fraught with contradictions,” said Gabor Kuszing, psychologist and a counsel for victims of domestic violence. “We are one of the worst countries in the EU for domestic abuse.”

He says that most of the time, women don’t even try to seek justice because of the legal odds of succeeding.

“Renner’s case is fairly common as per the psychological and physical abuse, but the fact that she fought in court is very rare.”

Over the course of his practice, Kuszing has discerned that there is an underlying problem with male attitude towards women.

“In the Renner case, the ex-boyfriend used violence to ascertain his power to show that he still had the upper hand. It was a story of a typically wounded male pride, a man who couldn’t swallow the consequences of his ex-girlfriend’s rejection.”

He says, the biggest issue is with traditional, sexist thinking that affects both young and old generations.

“There are many men who feel privileged and entitled to specific things down to their sex, so honestly, I don’t see anything positive for the future.”

He thinks that the government’s rhetoric is not helping.

“The Christian conservative narrative is dangerous, it clearly benefits men.”

This article is published as part of a project to promote independent digital media in Central and Eastern Europe funded by the National Endowment for Democracy and coordinated by Notes from Poland.